The first step in appreciating wildflowers is to explore the public lands. Wildflowers are easy to spot and nearly all natural areas have guidebooks for beginners. You can also call local botanical gardens and arboreta. Educational materials include plant identification books, coloring books, and trail guides to highlight the best ways to learn about and enjoy the wonders of our native wildflowers. Numerous guided walks, displays, and presentations are available from federal agencies and private organizations in order to aid you in your appreciation and understanding of the values of the wildflowers right under your nose! Please, don't pick the wildflowers.

Plants and plant communities are critically important to humans and their environment. Usually taken for granted, the role they play in our lives ranges from subtle to obvious.

Plants have great aesthetic value. How many of us would be willing to live without the plants beautifying the world around us? From the forests, woodlands, and grasslands surrounding our towns and cities to the wildflower gardens and natural landscaping in backyards, native plants provide a spiritual link between nature and our Nation's diverse cultural history. Many of the plants grown by gardeners are domesticated versions of wild plants. Many other gorgeous looking native plants have yet to be chosen for use in horticultural cultivation.

The oxygen in the air we breathe produced by the photosynthesis of plants. Not only is the air produced by plants, but the quality of the air can be greatly influenced by plants as well. Vegetation can restrict the movement of dust and pollutants, and plants, through their intake of carbon dioxide, can moderate the greenhouse effect resulting from the burning of fossil fuels.

Regional climates are influenced by plant cover. Forests and marshes, for example, can greatly moderate local climates. Natural disasters, such as drought, have been attributed to the destruction of forests and other critically important plant communities.

Diverse plant communities are extremely important for sustaining healthy ecosystems. When considering the complex interactions, such as the food web, that are found in ecosystems, you realize that every species counts! Plant habitats must be protected before species become critically endangered. With your support, we can conserve the more than 660 threatened and endangered U.S. plants and the 4,500 other U.S. plant species which are at risk of extinction.

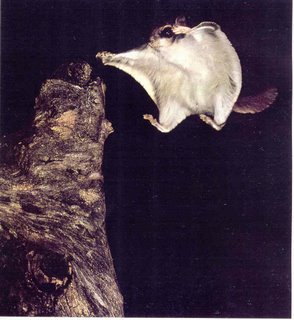

Plants and plant communities provide the habitat necessary to sustain wildlife and fish populations. Plant communities are the basis for virtually all terrestrial animal life because they provide the vital components of survival, food and shelter. The wildflowers you gaze upon aren't only beautiful, but useful as well, serving as animals' meals and homes. Without the appropriate habitat to support them, birds and animals of all kinds are in danger of extinction.

Although some 3,000 species of plants have been used by humans for food, 90 percent of the world's food comes from only 20 plant species. Three grass species in particular, rice, wheat, and corn, are by far the most important food plants in the world. If a new unmanageable disease or pest were to suddenly attack one of those species, an agricultural disaster could take place as a major food crop is destroyed. Luckily, the basis for stopping that kind of a disaster exists in the form of a genetic gold mine found in wild plants.

Native plants have great untapped potential as sources of improved genetic traits such as disease resistance, drought tolerance, and improved nutritional value. Have you ever admired the bright yellow or orange head of a sunflower? Breeding with wild species of sunflowers has produced the disease-resistant and highly productive hybrids used as the basis of the sunflower industry which provides seeds, oil and other products. So be sure to look with appreciation because the wild flower before you may have been one of the founding species of the $400 million sunflower industry.

Because they are food for animals, plants are the real source of animal products we consume - beef, chicken, and fish. Even dairy products such as milk and ice cream would not exist if dairy cows did not have grass and other plants to eat.

Plants are immensely important for the consumer goods they provide. Look around you. Fibers from plants provide clothing. The paper for documents, the cardboard in boxes, and the wood used to build our homes and offices depends on plants as well. From the spearmint in your toothpaste to the jojoba oil in your shampoo to floral perfume, plants have contributed to the things you find in your bathroom. Beyond the more obvious plant derived products surrounding you, it might surprise you that even future fuel needs may also be met by plants. Possible fuel sources include hydrocarbons derived from species like gopher plant or alcohols derived from corn and sugar cane. While many of the most important industrial products come from relatively common plants, rare and uncommon plants have provided exotic substances ranging from insect repellent to lubricants. Use as industrial products is yet another barely examined potential of plants.

Throughout history, plants have

been of paramount importance to medicine. You may not know it, but 80 percent of all medicinal drugs originate from wild plants. In fact, 25 percent of all prescriptions written annually in the United States contain chemicals from plants! In spite of the technological and medical advances in recent years, only 2 percent of the world's plant species have been analyzed for even one group of plant chemicals, the alkaloids. Any one of those plant chemicals could be useful. Take for example the pink flower, Madagascar periwinkle, from which vincristine is derived. Vincristine has increased the survival rate of children with leukemia from 20 percent to 80 percent. Another extremely promising drug is taxol, derived from the Pacific Yew, which has worked against a broad range of cancers, including ovarian cancer. As most plants remain untested for medicinal potential, many more such drugs remain to be found.

Plant communities form the basis for many important recreational activities, including hiking, fishing, and hunting, photography, and nature observation. Could you imagine fishing in a pool surrounded by concrete or photographing animals and birds in an asphalt parking lot? Without the plants creating the habitat as the backdrop for those activities, recreation simply would not be as enjoyable and aesthetically pleasing.

The delicate wildflowers and other plants that dot the hillsides through spring, summer, and fall protect the soil from rampaging rains as they have done for thousands of years. Without adequate plant cover and root systems holding it in place, wind or water will carry away the thin mantle of soil upon which our existence depends.

Plants are extremely important to the quality of the water we use. A diverse cover of plants aids in maintaining healthy watersheds, streams, and lakes by holding soil in place on the banks, regulating stream flows, and filtering sediments from water by slowing it down.

Conservation and Etiquette - The Dos and Don'ts of Wildflower Appreciation

Wildflowers are the jewels of the public lands. Like any treasure, they must be protected for all to enjoy. You can join the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service in the stewardship of these priceless resources.

• Take a hike and stop to smell the fragrant wild roses.

• Take only photographs and memories when you leave.

• Please, don't pick the flowers.

• Tread lightly and stay on the trail.

• Don't be afraid to ask for information on wildflowers.

• Get involved! Explore volunteer opportunities on your public lands.

There is still time to enjoy the wildflowers of the Blue Ridge!

Parkway bloom timesThe time frame references the usual dates a particular flower is in peak bloom.

• Angelica Aug-Sept

• Bellflower July-Sept

• Bergamot Beebalm July-Aug

• Bladder Campion May-Aug

• Blazing Star Aug-Sept

• Boneset Aug

• Bull Thistle late June-frost

• Butter and Eggs June-Aug

• Cardinal Flower Aug

• Coreopsis June-Aug

• Deptford Pink June-Aug

• False Hellebore June-Aug

• Gentian late Aug-frost

• Ironweed Aug

• Jewel Weed Aug

• Joe-Pye-Weed Aug

• Milkweed July-Aug

• Mullein June-Sept

• Nodding Lady Tresses Aug-frost

• Oswego Tea July-Aug

• Pokeberry Aug

• Queen Anne's Lace May-Sept

• Starry Campion July-Sept

• Tall Coneflower July-Aug

• Tree of Heaven June, (Berries July-Oct)

• Turkscap Lily June-Aug

• Virgins Bower Aug

All images taken on the Blue Ridge Parkway, August, 2006 by D L Ennis